In the first in our series of guest blogs Steven Toft - author and creator of Flip Chart Fairy Tales - takes a look at UKCES' latest report, Growth Through People: Evidence and Analysis, and asks what can be done about productivity in the UK?

The Growth Through People report published at the end of last month by the UK Commission for Employment and Skills (UKCES) contains some sharp words for Britain’s managers. Despite having a highly skilled workforce, the UK’s productivity has tanked. At least some of the reasons for this must be due to what is happening in the workplace.

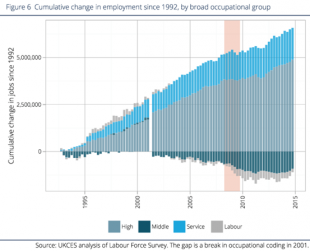

Much of the employment growth over the past two decades has come from high skilled jobs, defined here as managerial, professional and technical occupations. After a slight post recession dip, this trend continued during the recent recovery.

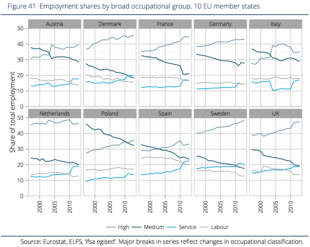

To an extent, something similar has happened in most advanced economies but the trend has been particularly marked in the UK, Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands.

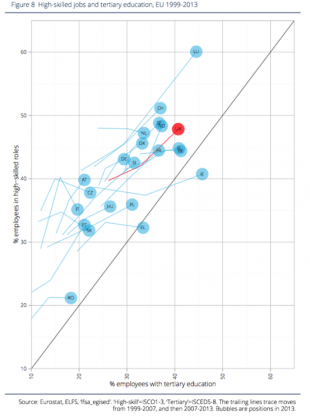

Compared to other EU countries, the UK has a high percentage of its workers in high-skill jobs and with tertiary qualifications.

Whatever else you might say about the UK, it’s not a low skill economy. So why, then, is our productivity so poor?

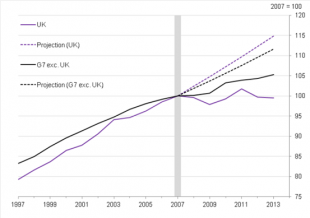

The UK’s productivity has lagged behind that of most comparable economies for some time but it was beginning to catch up. This changed with the recession. Once again, the UK’s productivity has fallen behind.

Figure 4: Constant price GDP per hour worked, actuals and projections

Source: ONS International Comparisons of Productivity, 20 February 2015

But we can’t blame this on low skills. The ONS reckons things would be even worse were it not for the higher skill level in the UK’s workforce.

Increasing skill levels played a large part in increasing the country’s productivity before the recession and have mitigated the effects of declining productivity since. Productivity has crashed in spite of the UK’s highly skilled workforce.

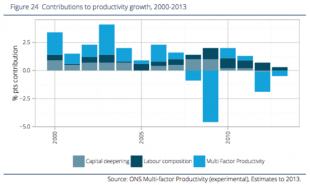

Much of the fall in productivity is due to what the ONS calls Multi Factor Productivity (MFP) or Total Factor Productivity (TFP):

Output growth which cannot be explained by increasing volume of inputs and is assumed to reflect increases in the efficiency of use of these inputs.

In other words, how resources like capital and labour are managed. As the Growth Through People report comments:

One big part of TFP is the ‘black box’ of the workplace, and how employers turn skilled workers and tools into products and services which customers value. We may have a more qualified and – if qualifications are of good quality – a more skilled workforce, but are those skills being used effectively? It seems that as world markets have become more difficult in the past decade, many of our work- places have struggled to adapt.

The inability to turn a highly skilled population into high productivity is a symptom of failure in the workplace.

An important backdrop to productivity performance is that we have a workforce which has never been so well qualified. If we have a better-educated workforce, then we have to look at how their talents are being applied: the workplace must have played a role in that productivity slowdown.

Research by the World Management Survey (WMS) has rated UK management practice as mediocre. As LSE’s Rebecca Homkes explains here, the UK’s score is dragged down by a long tail of under performing companies.

Cross-country differences account for less than 10% of the diverging management scores: the biggest management differences occur across firms within the same country. The distribution of scores highlights the fact that much of what drags certain countries down is a persistent ‘tail’ of underperforming firms, those that score less than a two on our five point scale. While this tail is largely absent in the United States, it is evident in the UK and especially pronounced in developing countries such as Brazil and India.

Our research shows that large and persistent gaps in management quality remain across countries, mainly driven by the tail of underperforming firms. The UK clearly has a deficit in management quality, and this deficit is likely to be a key factor explaining the persistent productivity gap with other countries such as the United States and Germany.

The WMS researchers estimate that a third of the difference in total factor productivity between the UK and the US can be accounted for by management practices.

The UK is suffering from “declining business dynamism”, says UKCES.

The evidence is that the UK has a variable business population, with a fair share of work- places managed at world-class levels, but also a long tail of businesses with weak management.

[T]oo many businesses seem in a ‘low skill equilibrium’, limiting their ambitions by organising work around a low level of skill. These businesses use the minimum necessary skill from their employees, rather than seeking to fully utilise their talents, or develop them further, to drive the business forward.

Poor productivity is not due to poor skills but to poor utilisation of those skills. The UK has too many low performance workplaces.

The evidence on overskilling and overqualification suggests that too many workplaces are leaving skills underused. Just as we saw in discussing the long tail of weakly managed firms and the growing low productivity businesses, there seem to be too many workplaces which use only the skills they need to fulfil their immediate requirements, and give no thought to what they could do with the full range of employees’ skills.

Even when companies are aware of this, says UKCES, too few of them are moved do anything about it.

[T]oo many workplaces are content to settle around ways of working optimised for the lowest possible skill level, allowing employee skills to go to waste for want of ambition. We see this through the long tail of management practice, limited action on management skills, and the levels of overskill and overqualification.

The evidence in Growth Through People raises some serious questions for many of Britain’s managers. With access to a highly skilled workforce and relatively unconstrained by regulation we might expect our economy to be more productive than many of its competitors. But instead, a lot of firms are cutting back on training and doing just enough to make a profit and get by. Too many are freeloading while Britain’s productivity slides and its wage levels fall.

Last year, Peter Cheese, the CEO of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development warned against taking the ‘low road’ of a low skill, low wage, low productivity economy. What we have now, though, is high skill, low wage low productivity economy. That’s not quite as worrying if our business leaders get better at managing and developing their people. At the moment, the evidence suggests that many of them have a long way to go.

Steven Toft is a business consultant, with more than twenty years experience of managing change in organisations. He has worked in more than thirty organisations, in various sectors, across Europe and the Middle-East. In 2007 he started a blog, ‘Flip Chart Fairy Tales’, writing about the world of work. In November 2013, the blog won the Editorial Intelligence Independent Blogger award.

This post gives the views of the author, and does not necessarily reflect the position of UKCES.

Leave a comment